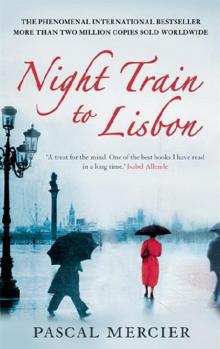

Night Train To Lisbon Book Pdf Download

Dark TRAIN TO LISBON

PASCAL MERCIER was built-in in 1944 in Bern, Switzerland, and currently lives in Berlin where he is a professor of philosophy. Dark Train to Lisbon is his third novel.

'Rich, dumbo, star-spangle … Night Train to Lisbon is about ends and means, language and loneliness, betrayal and complicity, intimacy and imagination, vanity and forgiveness.'

Harper's

'Have you ever been overwhelmed past an abrupt impulse to exit your old life behind and get-go a new one? Many of us feel the temptation; very few give in to it … Night Train to Lisbon is a novel of ideas that reads like a thriller: an unsentimental journeying that seems to transcend time and infinite. Every grapheme, every scene, is evoked with an unequalled economic system and a tragic nobility redolent of the mysterious hero … Pascal Mercier at present takes his rightful place amongst our finest European novelists.'

Sunday Telegraph

'I heartily recommend [this novel] … I too loved The Can Drum and Darkness at Apex and The Outsider. If those sound like your kind of novel too, Night Railroad train to Lisbon stands comfortably in that visitor.'

Irish Independent

'Mercier draws together all the great existential questions in a masterful novel.'

De Volkskrant

'A serious and beautiful book'

Le Monde

'A book of astonishing richness … A visionary writer … A deserved international hit.'

Le Canard enchaîné

'Powerful, serious, and brilliant … One of the genuine revelations of the year.'

L'Humanité

'One of the groovy European novels of recent years'

Page des libraires

'In this book, reading becomes experience … I reads this book almost breathlessly, almost unable to put it down … A handbook for the soul, intellect and heart. In reading information technology, 1 learns to value fourth dimension with a book: a rich, fulfilling lifetime.'

Die Welt

'A volume of manner, narrative depth and philosophy … I read it in three nights. Then I was convinced to alter my life.'

Süddeutsche Zeitung

'A sensation … The all-time book of the last decade … A novel of incredible clarity and beauty.'

Bücher

Copyright

Originally published in 2004 in Germany by Carl Hanser Verlag.

This edition originally published in the Us of America by Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This updated paperback edition published in U.k. in 2009

by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Carl Hanser Verlag Muenchen Wien 2004

The moral correct of Pascal Mercier to exist identified

as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Deed of 1988.

Translation © Barbara Harshav 2008

The moral right of Barbara Harshav to be identified

as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Human action of 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval organisation or transmitted in any form or by whatever means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior permission of both the copyright owner

and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it

are the work of the writer'southward imagination. Any resemblance

to actual persons, living or expressionless, events or localities,

is entirely coincidental.

The epigraphs are taken from:

Coplas de don Jorge Manrique by Jorge Manrique,

translated by Henry Longfellow (Boston: Allen & Ticknor, 1833)

The Complete Essays of Montaigne by Michel de Montaigne,

translated by Donald M. Frame (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1948)

The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa by Fernando Pessoa,

translated by Richard Zenith (New York: Grove Press, 2002)

First eBook Edition: January 2010

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond Firm

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Cover

NIGHT TRAIN TO LISBON

COPYRIGHT

Office I: THE Difference

Affiliate 1

Affiliate 2

CHAPTER iii

CHAPTER four

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER half-dozen

Chapter 7

CHAPTER 8

Affiliate 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

Chapter 12

Role II: THE ENCOUNTER

Affiliate 13

Affiliate 14

Chapter 15

Affiliate 16

CHAPTER 17

Chapter 18

Affiliate nineteen

CHAPTER twenty

Affiliate 21

Affiliate 22

Affiliate 23

Role III: THE Attempt

Affiliate 24

Affiliate 25

CHAPTER 26

Chapter 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

Affiliate xxx

Chapter 31

Affiliate 32

Chapter 33

CHAPTER 34

Chapter 35

Affiliate 36

CHAPTER 37

Affiliate 38

Affiliate 39

CHAPTER forty

CHAPTER 41

Affiliate 42

Chapter 43

Affiliate 44

CHAPTER 45

CHAPTER 46

Affiliate 47

Chapter 48

Office Iv: THE RETURN

Chapter 49

CHAPTER 50

CHAPTER 51

Affiliate 52

Nuestras vidas son los ríos

que van a dar en la mar,

qu'es el morir

Our lives are rivers, gliding gratuitous

to that unfathomed, boundless ocean,

the silent grave!

Jorge Manrique

Nous sommes tous de lopins et d'une contexture si

informe et diverse, que chaque piece, chaque momant, faict son jeu.

Et se trouve autant de departure de nous à nous mesmes,

que de nous à autruy.

We are all patchwork, and then shapeless and various in

composition that each flake, each moment, plays its own

game. And there is as much divergence betwixt us and

ourselves as between us and others.

Michel de Montaigne, Essays, 2nd Book, 1

Cada um de nós é vários, é muitos, é uma prolixidade

de si mesmos. Por isso aquele que despreza o ambiente não é o

mesmo que dele se alegra ou padece. Na vasta colónia exercise nosso

ser há gente de muitas espécies, pensando

e sentindo diferentemente.

Each of us is several, is many, is a profusion of selves. So that

the self who disdains his surroundings is not the same

as the self who suffers or takes joy in them. In the vast

colony of our beingness there are many species of people who

think and feel in dissimilar ways.

Fernando Pessoa, O Livro practice Desassossego

PART I

THE DEPARTURE

1

The day that concluded wi

th everything different in the life of Raimund Gregorius began similar endless other days. At quarter to eight, he came from Bundesterrasse and stepped on to the Kirchenfeldbrücke leading from the heart of the city to the Gymnasium. He did that every day of the school term, ever at quarter to eight. In one case when the bridge was blocked, he made a mistake in the Greek grade. That had never happened before nor did it ever happen again. For days, the whole school talked of null just this mistake. The longer the debate lasted, the more information technology was thought that he had been misheard. At last, this conviction won out even among the students who had been there. It was simply inconceivable that Mundus, as everyone chosen him, could make a mistake in Greek, Latin or Hebrew.

Gregorius looked alee at the pointed towers of the Historical Museum of the metropolis of Bern, up to the Gurten and downwardly to the Aare with its glacier-greenish water. A gusty air current drove depression-lying clouds over him, turned his umbrella inside out and whipped the rain in his face. It was then that he noticed the woman continuing in the middle of the bridge. She had leaned her elbows on the railing and was reading – in the pouring rain – what looked like a letter. She must have been belongings the sheet with both hands. Equally Gregorius came closer, she suddenly crumpled the paper, kneaded information technology into a ball and threw the ball into space with a trigger-happy motility. Instinctively, Gregorius had walked faster and was now simply a few steps away from her. He saw the rage in her pale, pelting-wet face. It wasn't a rage that could be expressed in words then blow over. It was a grim rage turned in that must accept been smouldering in her for a long fourth dimension. At present the adult female leaned on the railing with outstretched artillery, and slipped her heels out of her shoes. Now she jumps. Gregorius abandoned the umbrella to a gust of wind that drove it over the railing, threw his briefcase full of school notebooks to the basis and uttered a string of curses that weren't part of his usual vocabulary. The briefcase opened and the notebooks slid on to the wet pavement. The adult female turned around. For a few moments, she watched unmoving as the notebooks darkened with the h2o. So she pulled a felt-tipped pen from her coat pocket, took two steps, leaned down to Gregorius and wrote a line of numbers on his forehead.

'Forgive me,' she said in French, incoherent and with a strange emphasis. 'Merely I mustn't forget this telephone number and I don't have any paper with me.'

At present she looked at her easily equally if she were seeing them for the commencement time.

'Naturally, I could accept …' And at present, looking back and along between Gregorius'southward forehead and her manus, she wrote the numbers on the dorsum of the hand. 'I … I didn't want to keep it, I wanted to forget everything, but when I saw the letter fall … I had to hold on to information technology.'

The pelting on his thick glasses muddied Gregorius's sight and he groped awkwardly for the moisture notebooks. The tip of the felt pen seemed to slide over his forehead again. But so he realized it was the fingers of the woman, who was trying to wipe away the numbers with a handkerchief.

'It is out of line, I know …' And now she started helping Gregorius gather up the notebooks. He touched her hand and brushed against her knee, and when the 2 of them reached for the final notebook, they bumped heads.

'Cheers very much,' he said when they stood facing each other. He pointed to her caput. 'Does it injure?'

Absently, looking down, she shook her head. The rain beat down on her pilus and ran over her face.

'Can I walk a few steps with you?'

'Ah … yes, of course,' Gregorius stammered.

Silently they walked together to the end of the bridge and on towards the school. His sense of time told Gregorius that information technology was afterward eight and the first class had already begun. How far was 'a few steps'? The woman had adjusted to his stride and plodded along beside him every bit if she might follow him all day. She had pulled the broad collar of her glaze then high that, from the side, Gregorius could only see her brow.

'I accept to go in here, into the Gymnasium,' he said, stopping. 'I'grand a teacher.'

'Can I come along?' she asked softly.

Gregorius hesitated and ran his sleeve over his wet glasses. 'Well … it's dry out there,' he said at concluding.

She went upwards the stairs, Gregorius held the door open for her, and then they stood in the hall, which seemed especially empty and tranquillity at present that classes had started. Her coat was dripping.

'Expect here,' said Gregorius and went to the cloakroom to get a towel.

At the mirror, he stale his glasses and wiped his face. The numbers could still be seen on his brow. He held a corner of the towel under the warm water and was about to kickoff rubbing them out when he suddenly stopped. That was the moment that decided everything, he thought when he recalled the event hours afterward. That is, he realized that he really didn't want to wipe abroad the trace of his see with the enigmatic adult female.

He imagined actualization earlier the form with a phone number on his face, he, Mundus, the most reliable and predictable person in this edifice and probably in the whole history of the school, having worked here for more than thirty years, impeccable in his profession, a pillar of the institution, a little boring perhaps, but respected and even feared in the university for his astounding knowledge of ancient languages. He was affectionately teased by his students who put him to the examination every twelvemonth by calling him in the middle of the nighttime and request near some remote passage in an aboriginal text, only to receive data that was both dry and exhaustive, including a critical commentary with other possible meanings, all of information technology presented without a trace of anger at the disturbance. Mundus, a man with an impossibly erstwhile-fashioned, even archaic first name that you merely had to shorten, and couldn't shorten whatever other way. It was a name that perfectly suited the character of this man, for what he carried around in him as a philologist was in fact no less than a whole world, or rather several whole worlds, since along with those Latin and Greek passages, his head also held the Hebrew that had amazed several Quondam Attestation scholars. If you lot want to run into a true scholar, the Rector would say when he introduced him to a new class, here he is.

And this scholar, Gregorius thought now, this dry out human being who seemed to some to consist only of dead words, and who was spitefully called The Papyrus by some colleagues who envied him his popularity – this scholar would shortly enter the classroom with a telephone number written on his forehead by a desperate adult female apparently torn between rage and honey, a woman in a cherry leather coat with a soft, southern vocalism that sounded like an countless hesitant drawl that drew you lot in merely past hearing it.

When Gregorius had brought her the towel, the woman had used information technology to rub her long black hair, which she had then combed back so that it spread over her coat neckband similar a fan. The janitor entered the hall and, when he saw Gregorius, cast an amazed wait at the clock over the exit and and then at his lookout man. Gregorius nodded to him, as he always did. A pupil hurried past, looked back in surprise and went on his fashion.

'I teach up there,' Gregorius said to the adult female and pointed up through a window to some other office of the edifice. Seconds passed. He felt his eye trounce. 'Do you want to come up along?'

After, Gregorius couldn't believe he had really said that; but he must have done, for he recalled the screech of his safety soles on the linoleum and the clack of the woman's boots as they walked together to the classroom.

'What's your mother tongue?' he had asked her.

'Português,' she had answered.

The o she pronounced surprisingly as a u; the rising, strangely constrained lightness of the é and the soft sh at the end came together in a tune that sounded much longer than it really was, and that he could have listened to all day long.

'Wait,' he said, took his notebook out of his jacket pocket and ripped out a folio: 'For the number.'

His hand was on the doorknob when he asked her to say Português once again. She repeated it, and for the first time he saw her smile.

The chatter bankrupt off abruptly when they entered the classroom. Instead, an amazed silence filled the room. Later, Gregorius remembered the moment precisely: he had

enjoyed this surprised silence, the look of incredulity on the faces of his students as they gazed at the decrepit couple in the doorway. He had besides enjoyed his delight at being able to feel in a way he would never accept believed possible.

'Perhaps there?' said Gregorius to the adult female and pointed to an empty seat at the dorsum of the room. So he avant-garde, greeted the class equally usual, and sabbatum down behind the desk. He had no idea how he could explain the woman's presence and so he just had them translate the text they were working on. The translations were halting, and he defenseless some bewildered looks among the students for he – he, Mundus, who recognized every mistake, fifty-fifty in his sleep – was at present overlooking dozens of errors.

He tried not to look at the woman. Still, every time he did and so, he was struck by the damp strands of hair that framed her face, the white clenched hands, the absent, lost look every bit she gazed out of the window. Once she took out the pen and wrote the phone number on the page from his notebook. Then she leaned back in her seat and hardly seemed to know where she was.

It was an incommunicable state of affairs and Gregorius glanced at the clock: ten more minutes until break. Then the woman got up and walked softly to the door. When she reached information technology, she turned round to him and put a finger to her lips. He nodded and she repeated the gesture with a smile. So the door closed behind her with a soft click.

From this moment on, Gregorius no longer heard anything the students said. It was as if he was completely alone and enclosed in a numbing silence. He found himself standing at the window and watching the adult female in the red glaze until she had disappeared from view. He felt the effort not to run after her reverberate through him. He kept seeing the finger on her lips that could mean so many things: I don't desire to disturb you, and Information technology's our secret, merely also, Let me go at present, this can't go on.

When the bong rang for the break, he was yet continuing at the window. Backside him, the students left more quietly than usual. Later he went out too, left the building through the back door and went across the street to the public library where nobody would await for him.

For the second part of the double class, he was on time equally always. By then he had rubbed the numbers off his brow, after writing them down in his notebook, and the narrow fringe of grey hair had stale. But the damp patches on his jacket and trousers revealed that something unusual had happened. Now he took the stack of soaked notebooks out of his briefcase.

DOWNLOAD HERE

Posted by: taylorroughtne.blogspot.com

0 Comments